While scanning through hundreds of vintage magazines looking for classic advertising I often come across interesting items that cause me to pause. Internal magazine stories are difficult to market but also difficult to pass by. These will mostly be stories on 1950s celebrities and athletes. I hope you find something you like.

Yours truly,

Toronto Star Weekly

March 24, 1956

Found this photo online that was missing from my checklist for the Star Weekly hockey photo series. I’ve added it to the checklist which you can view

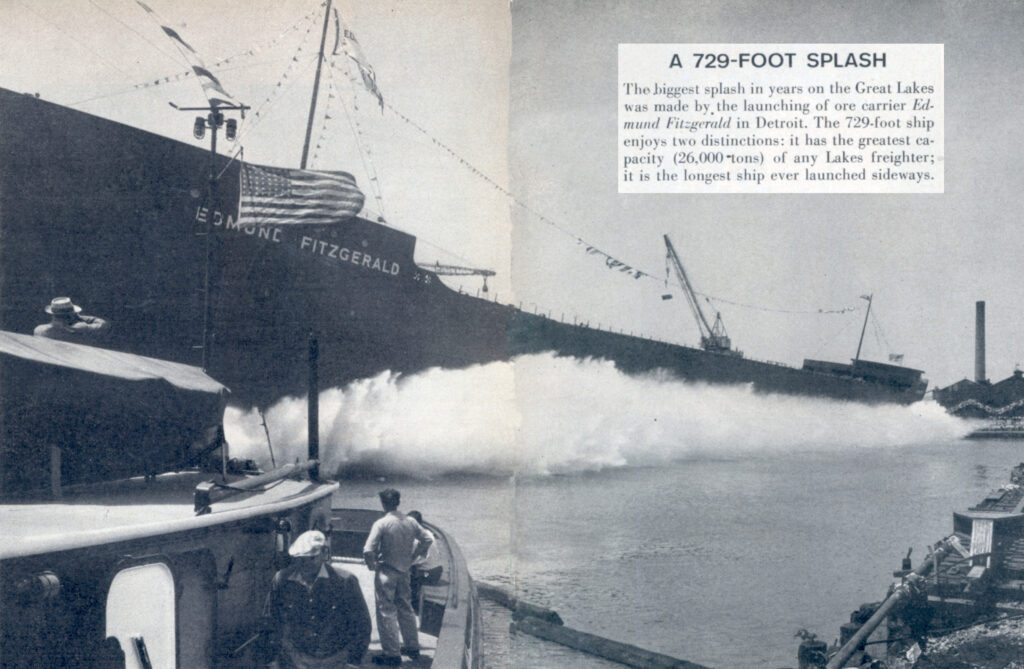

Life Magazine, June 23, 1958

Launching of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Back to

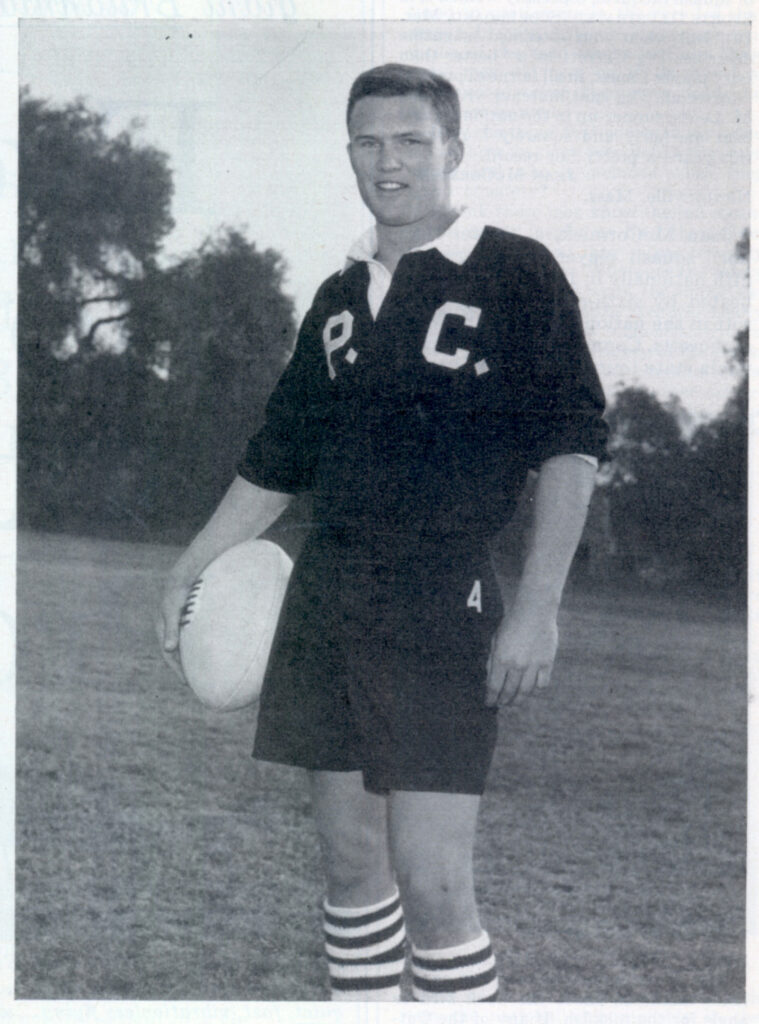

Sports Illustrated, March 31, 1958

Kristoffer Kristofferson

This dashing young man in the Rugby outfit plays standoff on the team at Pomona College in California, where he is a senior. But this is only a small facet of 21-year-old Kris Kristofferson’s amazing record. He is also starting left end on the varsity football team, a Golden Gloves boxer, sports editor of the college paper, outstanding cadet in the ROTC battalion of which he is cadet commander. As an English major he is an honor student and member of the four-man senior honor society on campus. Kris won four of the top 20 awards recently given in a creative writing contest for college students. He composes folk songs which he sings to his own guitar accompaniment. And to crown this varied list of accomplishments Kris is a Rhodes scholar-elect, one of 32 young Americans chosen to go to Oxford this fall. As the eldest of three children of Major General and Mrs. Henry Kristofferson, Kris will find travel familiar. The family has done a lot of it keeping up with their airline-executive father (the senior Kristoffersons are in Saudi, Arabia, where the general is operations manager for Aramco Airlines), and Kris has lived in Texas, Washington, New York and California. It was in San Mateo that he attended high school and distinguished himself as a distance runner. At Oxford he will study English literature to prepare for a writing career.

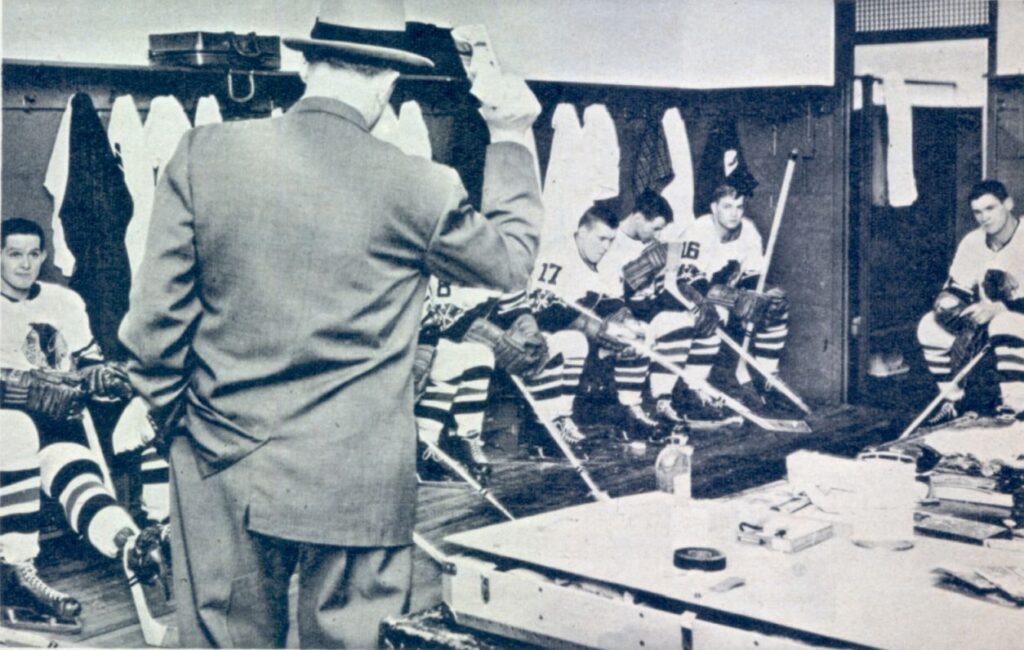

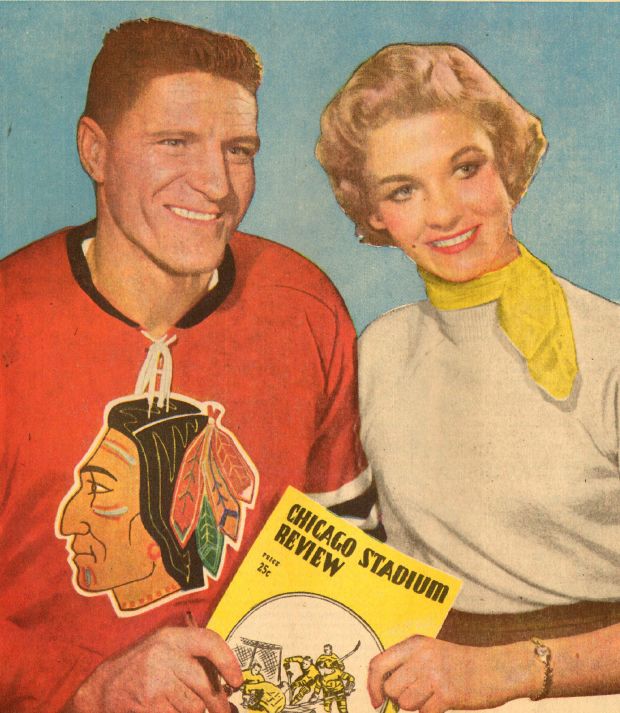

Toronto Star Weekly, Feb. 1958

Chicago Black Hawks coach Rudy Pilous had been on the job less than a month when this photo by Robert Lansdale appeared in the Toronto Star Weekly in February 1958. Bobby Hull in his rookie season can be seen next to the doorway wearing number 16.

Life Magazine, 1946

In a 1946 issue Life Magazine provided this photo chart of Hollywood’s top-ten box office stars from 1936 through 1945 (click on photo to enlarge chart)

Toronto Star Weekly, Sept. 30, 1950

Trigger, The Long Tailer, has a $25,000 Trailer

DOM DIMAGGIO Baseball’s Greatest Outfielder

In a 1948 issue of Look Magazine sportswriter Tim Cohane postulated that Boston Red Sox center-fielder Dom DiMaggio was baseball’s greatest outfielder.

To illustrate his claim Cohane presented a photo of the spacious outfield area of New York’s Yankee Stadium. It was marked to show the limits of Dom’s range in all directions.

Just as interesting as Cohane’s claim, however, is the photo of the old stadium itself (click on photo for a closer look). It shows only two monuments in centerfield for Miller Huggins and Lou Gehrig. Babe Ruth’s monument had yet to appear (he died in August 1948). Also interesting is the differing heights of the outfield wall and the mangy looking condition of the ballpark grass.

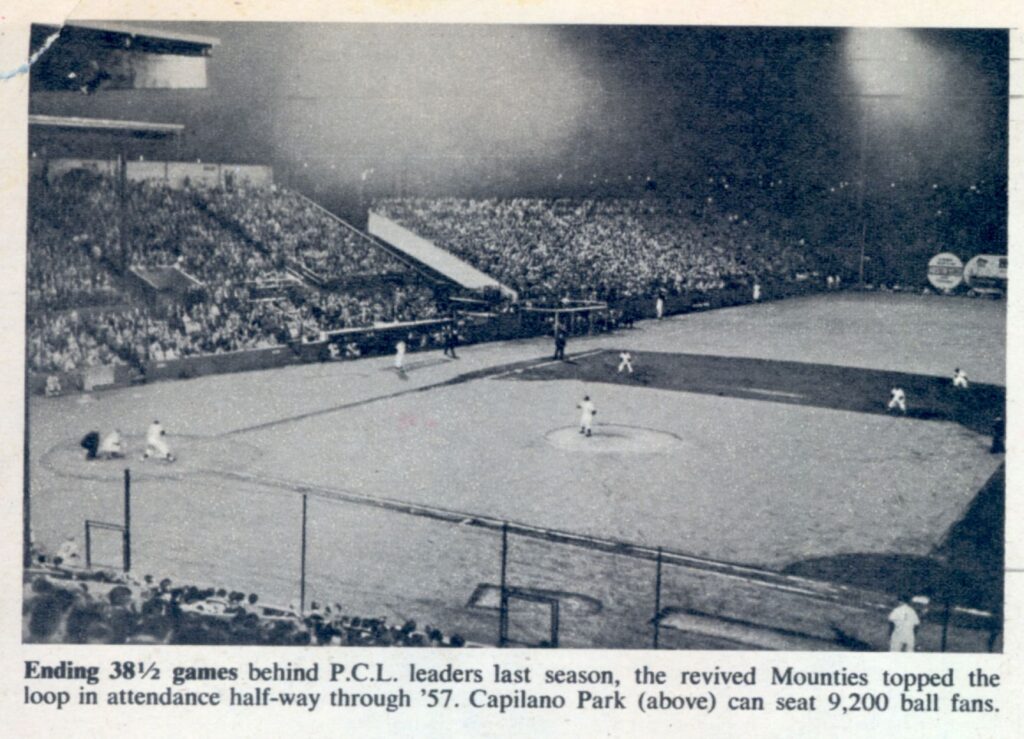

Hall of Fame sportswriter Andy O’Brien was excited about the rebirth of baseball in Vancouver in 1957.

Up Bounced a Business

By Robert M. Yoder

Dec. 21, 1946

The Saturday Evening Post

The case of R. T. James and his walking spring proves that a man who will work hard and well can get someplace, thanks to a trivial little accident he is almost too busy to notice. It further proves that if a father brings a first-class engineering education to bear on a problem, that question can be solved by his two-year-old son at play. James is a marine engineer, Penn State ’39, and eighteen months ago was barking intently to the mighty machinery of battleships and cruisers. A “guarantee engineer,” he

represented the builders on the shakedown cruises of many famous fighting ships. To keep a torsion meter free from vibration, in testing the horsepower delivered by the great steel propeller shafts, the engineers suspended it by a spring. Of all the machinery that makes up a big ship’s muscles, this little spring has turned out to be the most important to James.

He knocked one off his desk one day ashore, and noted idly that it bounced around like a tumbler. Put on an inclined plane, it would walk down, like an acrobat doing slow flips, looking like some futuristic steel worm of the twenty-first century. James‘ son, Tommy, liked one as a plaything. So did a neighbor boy who came down with measles. So did other children. The engineer had a vague feeling that he ought to do something with this device, but it was Tommy who showed him the possibilities. The boy put one on the steps of their home, pulled the top of the spring down to the next step, and to James’ surprise this talented hardware walked gravely down, throwing itself into a loop, it landed on its head, lifted its tail, threw itself sedately into another loop to reach the step below. James immediately set out to design a toy in which this trick would be perfected.

Slinky Has Done Very Nicely by its Inventor

A piston-ring company manufactured a few for him in the fall of 1944, but toy dealers weren’t interested. Less than a month before Christmas a department store phoned to say James could use the end of one counter, but would have to serve as salesman. No little embarrassed, he and his wife turned clerks on November twenty-seventh and sold their entire supply – 400 – in ninety minutes. In the last few weeks of the year the toy made more money for them than James had earned all year in a good engineering job. By Christmas 22,000 had been sold, and by October of this year James was manufacturing 22,000 a week. He had sold 430.000, had his own business, his own little factory, and had quit marine engineering cold.

The toy he designed is not technically a spring, but a coil. A flat ribbon of steel seventy-nine feet long is wound so that the loops have zero tension or compression-—a Monday condition in which they would as soon fall together as fall apart. The result—called “Slinky”- looks like a stack of piston rings. That’s all there is to it, yet at a dollar a copy Slinky has performed very handsomely for its inventor. With the proceeds of an idea that fell off his desk, the thirty-year-old Philadelphian not only is launched on a manufacturing career which he likes very much, but could afford a little flier at a sport tried out last summer at Atlantic City. Sporting bloods who will gamble with anything were racing Slinkys.

LOUIS JAQUES: The Man Who Shoots Stars

Vol. 9, No. 2, 1959

Weekend Magazine

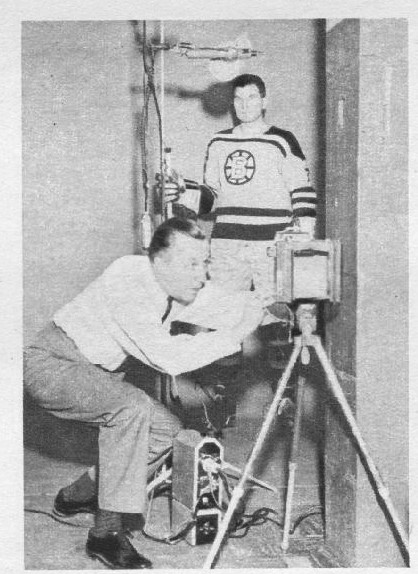

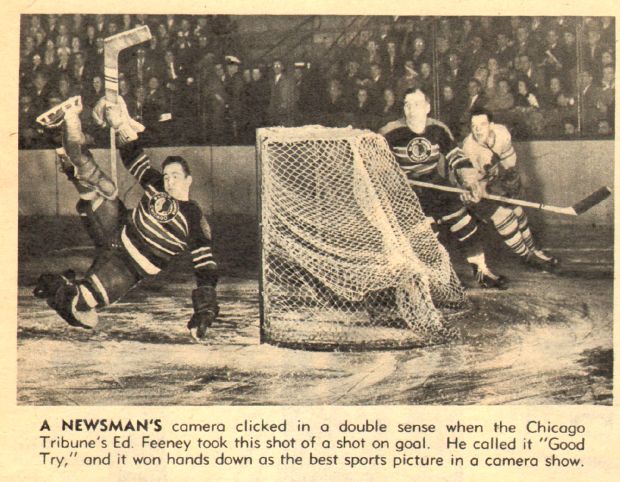

Staff Photographer Louis Jaques who, between many other assignments, takes our pictures of hockey and football stars, has long been recognized as one of Canada’s top photographers. And though Jaques swears he has no trade secrets, we’re willing to bet he sneaks psychology books from the library when no one is looking.

Peripatetic Jaques readies his camera for photograph of Boston Bruins’ Vic Stasiuk

For instance: Jaques was in Detroit to photograph Gordie Howe and Ted Lindsay (when Lindsay was still with the Red Wings) and had set up shop in a back room at the Olympia. When all was ready, he called in the two players. Because athletes are sometimes wary of any long-hair treatment, Jaques tried to put them at ease with their own brand of raillery.

However, as soon as he turned his cameras on Lindsay, he realized he had troubles. For Lindsay is one of those people with a crooked smile that is both charming and becoming until photographed. Jaques felt he couldn’t bring this to Ted’s attention for fear of making him self-conscious and thereby exaggerating the smile. It was one of those occasions that called for psychology.

Fortunately, Howe suddenly piped up with, “Come on, Lindsay, is this the first time you ever had your picture taken? Stand up straight, relax, don’t show that silly grin . . .” Both Jaques and Lindsay howled.

Said Jaques then to Lindsay, with a wink. “Here we’ll let the expert take over.”

Going along with the gag, Gordie began barking at Ted and clicking the shutter. Whose picture of Lindsay eventually appeared in WEEKEND? Howe’s, of course.

Because of all the equipment he has to tote around, Jaques contends his work calls for more muscles than psychology. Included in his travelling studio are four or five cameras. lenses of all sizes and shapes, filters, floodlights, eight-foot rolls of colored paper (for backgrounds) and his distinctive white umbrellas, which he uses as reflectors.

Once, during his trans-Canada tour taking pictures of football stars, Jaques – his studio in tow – found himself with but 24 hours in Toronto to photograph lineman John Welton, an all-star Argonaut for two years.

To his dismay, Jaques found that Welton was in hospital. Since his schedule was so tight, he decided to take a chance, anyway. He rushed to the hospital to find Welton with his leg suspended in a maze of ropes, pulleys and weights. Would it be possible, Jaques wondered aloud, to stand upright on one peg? Sure, answered Welton, only it would have to be done before 3 P.M. when his leg was to be put in a cast. Jaques then checked with the doctor, who reluctantly gave his O.K.

The next problem was to get Welton into uniform. The team’s uniforms were at the cleaner’s. Jaques phoned. The cleaner replied, yes, he would do his best to have one uniform ready by 3 P.M.

Jaques met the cleaner half-way to the hospital and rushed back with the uniform. Welton struggled into it. Then Jaques found there wasn’t enough space in the hospital room for his forest of equipment. He appealed to the matron. “Well, if you must,” she said, “you may use the corridor.”

Jaques finally got set up, Welton was wheeled to the appointed spot and propped up in place. Jaques clicked away, apologizing to people trying to get past in the corridor. It was a good picture, too, only this was the end of the season and the next year Welton was dropped from all-star rating and thus never did get into WEEKEND – an omission we remedy, with apologies, today.

Toronto Star Weekly, April 2, 1955

When Leapin’ Lou comes on the ice, he’s greeted with a mighty roar, for fans know they’ll see opposition players strewn about like ten-pins

By Jim Proudfoot

Mar. 3, 1956

Toronto Star Weekly

The Great Cover-Up

By Arthur W. Baum

May 31, 1947

The Saturday Evening Post

If any super-Babe ever really makes good the slugger’s habitual threat to knock the cover off the ball, it is going to be a black day for the Pennsylvania town of Perkasie, population 4121. Perkasie is represented, if unnamed, at every American, National, International. AA, Texas. Southern and other league game in which the official major-league

ball is used. A bit of Perkasie is on the fast ones, the floaters, the hooks, the hops. Perkasie rides from bat to fence, base to base. Perkasie thinks the most important thing about the horsehide is . . . the horsehide. Perkasie, in short, puts the covers on every ball used in every major-league game and in thousands of others.

Specifically, the family firm of Edward Hubbert & Son, lnc., is the horsehide monopolist. There are three Hubberts in the business, additional Hubberts at three Perkasie homes. They are locally noted for music. Every Hubbert plays, sings and dances. and any three Hubberts at any given time are a vaudeville act.

This year the firm will cover 1,000,000 baseballs – National League balls under the Spalding name, American under the A. J. Reach name – same ball exactly. Each major league will consume 5000 dozens and help out its farm teams with at least a couple of thousand dozens.

The baseballs belong to A. G. Spalding & Sons, and are covered by contract. A very delicate job it is. The horsehide alone is worth more than the inner ball. All stitching is hand done, 108 stitches in each ball, eighty-eight inches of waxed left-twisted twine on each needle. A good stitcher can cover about six baseballs an hour, -and one horse provides four dozen baseball covers. Unless he was branded or liked to scratch himself on barbed wire. Imperfections won’t pass an umpire.

The two hour-glass-shaped pieces of hide which cover each ball must match in thickness and have to be shaved to the close vicinity of fifty five thousandths of an inch. If he could maneuver it, which he can’t, Ed Hubbert could ruin a home-run king’s reputation by seeing to it that he had to hit a ball whose cover was only ten thousandths thicker than regulation. The difference would be worth at least seventy-five feet per hit.

Before 1928 the National League used a cover sixty thousandths of an inch thick and a five-strand thread, against the American League’s fifty thousandths and four-strand thread. This led to controversy over the higher seam and deader action of the National hall. In 1928 a compromise ball was made standard for both leagues, but the lively ball controversy goes on forever, complicated somewhat by the fact that left-field fences vary in distance from home as parks vary. Hubbert doesn’t care, and doesn’t even know which of the baseball; he covers carries which name. They are all five and one eighth ounces in weight and nine and one eighth inches in circumference. Know where the stitching starts and ends? At the upper right. hand comer of the ball. The Hubberts, and most of the 400 stitchers they have trained in thirty years of covering, know exactly where that is and can pick out those lost ends of waxed cotton twine that seem not to exist. Don’t worry about them. They are in there, deep in the hall, and they will be the last to come loose.

The two pieces of each cover come from the cutter with the thread holes spaced by algebraic formula to allow for the varying tensions around the curves. The wound ball inside is covered with a sticky plastic, and when the stitching is completed the seams are flattened.

Thirty years ago Ed Hubbert, then employed by A. J. Reach & Company in Philadelphia, moved to Perkasie and set up his workshop in his kitchen.

Today he has a factory. About 200 people are involved in the great cover-up, some of them working at home on near-by farms.

Every big-leaguer necessarily has his hands on Hubbert’s handiwork every time the play is his way. But not one major-league ballplayer has ever been inside the Hubbert factory.

At the National Hockey League “closed” practices you find

There’s More To “Big Time” Coaching

By Andy O’Brien

Jan. 7, 1961

Montreal Standard

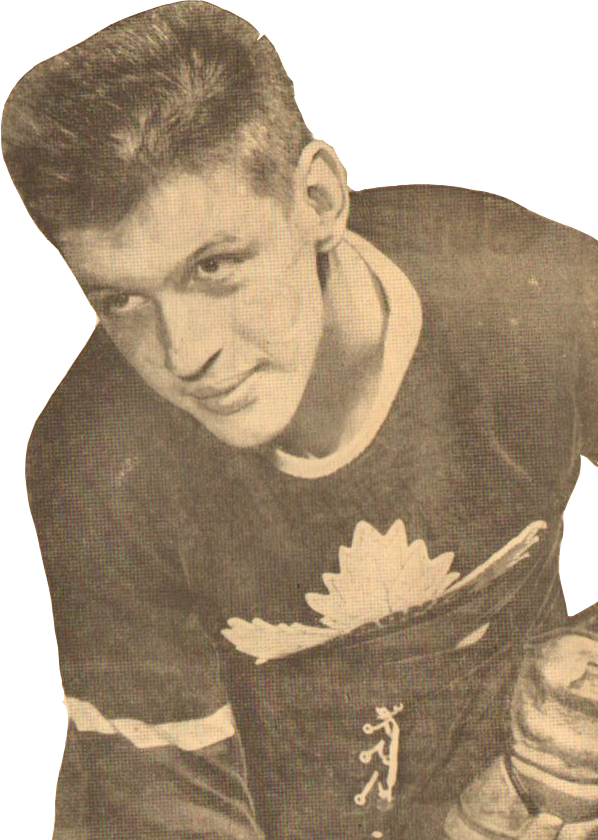

Toronto Star reporter William Drylie predicted big things for Eric Nesterenko in this 1954 article.

ERIC NESTERENKO: Another Conacher Coming Up?

Though observers differ in their ideas as to who Nesterenko looks like and what he will produce, all admit ‘he looks NHL’

GLENN HALL:

Meet the Wings’ New Goalie

Big things were in store for Glenn Hall when he hit Detroit’s farm system and now, his apprenticeship over, he’s setting a hot pace

By Jim Proudfoot

Feb. 4, 1956

Toronto Star Weekly

A year or so after this story appeared in March 1962, the NHL made a rule prohibiting players from cutting the palms out of their gloves. It is often referred to as the Carl Brewer rule.

This trading-est and buying-est team engineered probably its best deal in purchasing Red Sullivan, who stepped up from minor league hockey to gain recognition almost overnight as a top NHL centre

Back to